Share of voice is nearly useless as a measurement because the media landscape is larger and more fragmented than ever, but share of voice metrics fail to take the landscape into account.

I’ve seen no fewer than a dozen dashboards and Powerpoint slides recently which reference share of voice as a marketing KPI. Other than making things up, I can’t think of a worse KPI for marketing.

First, share of voice is a function of media, not marketing. It belongs in the realm of advertising and PR.

Second, share of voice is a nearly useless measurement in today’s media landscape. The average share of voice conversation goes something like this:

“Out of 3128 social media conversations mentioning us and our competitor, our brand had 15% share of voice. We are (awesome/terrible)!”

Why is this nearly useless? Share of voice suffers from what we measurement folks call denominator blindness. Denominator blindness is a lack of perspective on our part. For example, we might read a headline in the news which says “150 vaccinations last year had serious side effects!”. What’s left out of the story is the denominator: 150 out of 10 million annually. When you apply a denominator, suddenly the story becomes far less compelling.

How does denominator blindness impact share of voice?

Consider the above example. Suppose we were a local coffee shop and we were measuring our share of voice against a major chain coffee shop. We netted 15% share of voice out of the mentions of us vs. our competitor, or 469 mentions. That’s great, isn’t it?

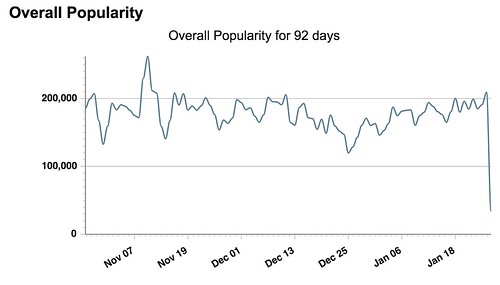

Except… on the topic of coffee alone, hundreds of thousands of people talk about coffee daily:

Our competitor AND our shop combined amount to less than 1.5% of the conversations about the topic. That’s one of the denominators we’re blind to – and it’s not the biggest one.

Let’s expand the denominator further. By recent estimates, we are sending more than half a million Tweets a minute. We watch almost 3 million videos on YouTube a minute. We update Facebook 300,000 times per minute. We load more than 100,000 photos to Instagram a minute.

469 mentions of our coffee shop are insignificant compared to the vast, ever expanding media universe.

Share of voice made a great deal of sense when there were 3 television networks, a handful of local radio stations, and a few hundred newspapers. We could accurately measure our portion of the entire media universe at the time. Today, with apps like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger sending millions of unobservable messages, combined with public social and digital feeds, we can no longer know what the total landscape is, much less measure our portion of it.

What should we measure? Continuous improvement – kaizen, in Japanese. If we netted 469 mentions today, try for 470 tomorrow. Focus on what we can do to grow our tiny patch of land, our tiny empire, a little more every day, every week, every month.

We compete for the attention of our audiences against our competitors, against apps and games and mass media and the rest of the world clamoring for the same slice of attention. Rather than worry about whether our competitor has a bigger slice, worry about holding onto and growing the slice we have.

You might also enjoy:

- You Ask, I Answer: Legality of Works in Custom GPTs?

- Almost Timely News: Recipes vs. Principles in Generative AI (2024-03-03)

- Almost Timely News, February 11, 2024: How To Evaluate a Generative AI System

- Mind Readings: Generative AI and Addition vs Substitution of Jobs

- Mind Readings: What Makes A Good Conference/Event?

Want to read more like this from Christopher Penn? Get updates here:

Take my Generative AI for Marketers course! |

Leave a Reply